Our collaboration with Mongabay-India began in October 2021, with the objective of enhancing their stories with our spatial analysis expertise. This blogpost documents the articles we’ve worked on together from July 2022 till the present.

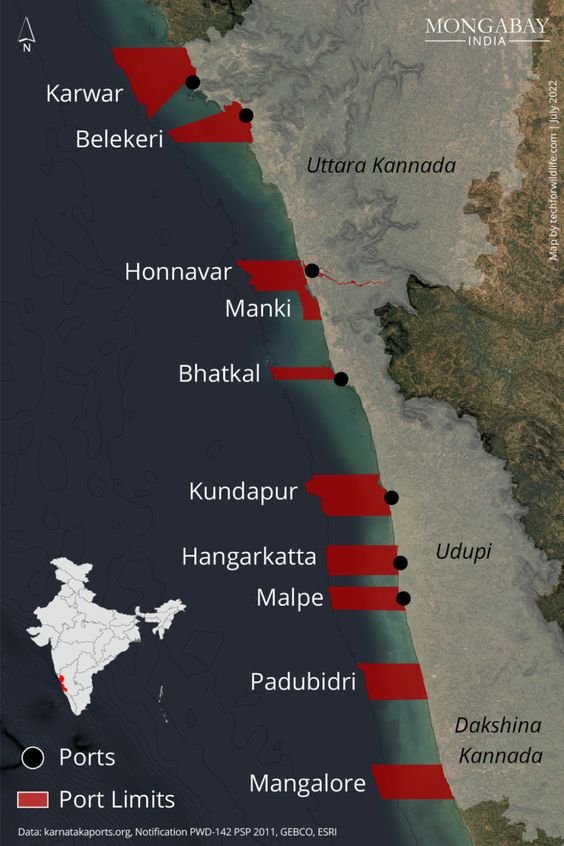

Karnataka’s port-development spree ignores coastal communities’ concerns

Karnataka is accelerating its port-led model of development in an attempt to attract investors to the state. However, this strategy impacts those who live close to the site of proposed developments. At least three ports currently being built have encountered issues due to community opposition.

The state has one major port and 12 minor ports under different stages of development; the map locates these ports and their port-limits. This was the first in a three-part story on port development in Karnataka.

A road for a port cuts through the livelihoods of fisherwomen in Uttara Kannada

The second story in a three-part story on port development in Karnataka focused on the proposed port at Honnavar, where a road of around four kilometres long is being constructed. The entire stretch is the fish-drying ground of the coastal communities, and part of the proposed road also cuts through forest land.

As part of the village coastal commons, they have been used by fishers over generations for drying fish; construction of the road would impact the livelihood of over 2,000 community members.

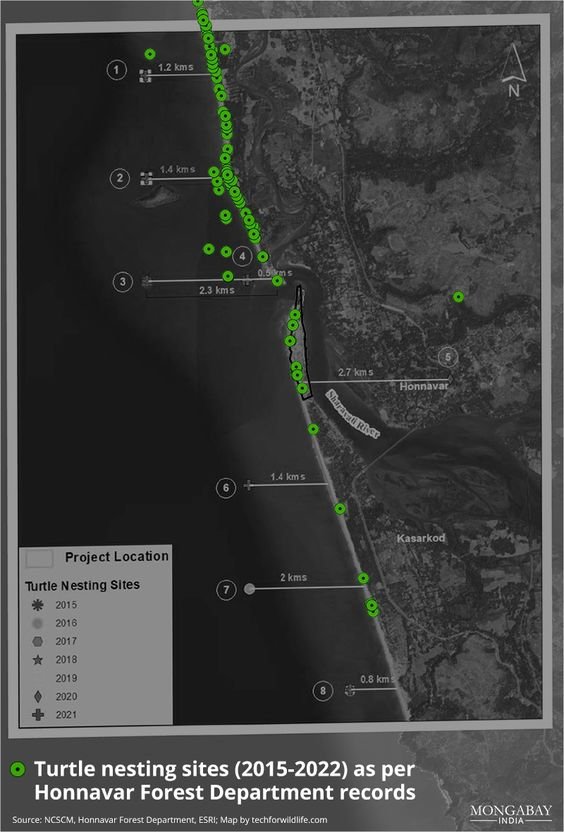

An upcoming port in Karnataka is shrinking space for olive ridley turtles

The last story in the three-part story on port development in Karnataka lists the discrepancy between the turtle nesting sites as reported by the Honnavar Forest Department, and that presented to the public by the National Centre for Sustainable Coastal Management (NCSCM). In brief, the NCSCM actually indicates that the turtle nesting sites are in the Arabian Sea; Olive Ridley turtles, like all sea turtles, nest on land. Our analysis indicates that the NCSCM made a basic conversion error when converting latitude-longitude pair values from one format to another, which was not identified before publication of their report.

Stubble burning is back, smothering north India with concerns for the upcoming winter

One of the main causes of air pollution over the national capital region (NCR) and other areas of the Indo-Gangetic plains has been stubble burning. This is the practice of setting fire to straw stubble to clear fields before the new crop is seeded. The story notes that the number of incidences of stubble-burning so far is greater than it was at this time last year, despite claims by officials that they are prepared to handle the now-annual catastrophe.

We prepared a visualisation using spatial data on fires and consequential PM 2.5 levels in the region, with each red pixel representing an area that contains actively burning fires. The grey pixels indicate PM 2.5 levels, the darker pixels leaning towards severe AQI.

Mizoram youth protest against the national highways widening project

The National Highways and Infrastructure Development Corporation (NHIDCL) has been criticised by environmental activists in Mizoram for ignoring environmental rules and regulations when working on highway projects in the state. According to the environmentalists, these initiatives have negatively impacted the environment, including damaging the state's water resources. The map we created to accompany this story depicts the four national highways in the state where the NHIDCL is currently carrying out widening work.

(Note: This is the sixth blog in the series, on our collaboration with Mongabay-India. Read the previous blog here, and the first in the series, here.)