(Cross-posted from the Hindu Business Line, December 6th 2011)

Technology magnifies human intent and capacity.” — Dr Kentaro Toyama

Knowledge of the spatial nature of one's surroundings is essential for resource use, environmental management, allocation of land rights and diplomatic relations with other communities.Today, India is in transition; there are numerous independent agents with differing aims and objectives attempting to access the nation's natural resources. The increased workload on environmental regulatory agencies has led to a profusion of procedures that curtail economic growth and governmental transparency.

In particular, the protection of India's environment and forests requires the processing of large amounts of geographic information as well as numerous levels of bureaucratic approval. Integrating a decision support system with a Geographic Information System (GIS) — which integrates different datasets and provides users with the ability to compare features across spatial datasets with different origins — could improve environmental regulation in India.

Traditionally, geographic information was collected by teams of field surveyors, and recorded in physical media in the form of maps. Land-cover data regarding tree cover and agricultural lands, physical features such as mountains and rivers, or even virtual data such as the location and extent of borders and boundaries qualify as geographic information.

Surveying, the science of determining the location of points on the earth's surface, and cartography, the complementary science of creating maps with this information, are ancient fields of study. Teams of surveyors would spend years determining land ownership boundaries and physical features, and highly trained cartographers would record the geographic information of entire communities in the form of detailed maps.

India has a long historical tradition of collecting and recording geographic information. One of the first and largest land surveys was conducted by Sher Shah in the sixteenth century for the purpose of land revenue estimation. Mughal emperor Aurangzeb duplicated this task in the late seventeenth century and the British Empire continued this exercise, using a system of written records and field maps to establish control over the land it acquired.

Role of satellites

This exercise of information collection and analysis required trained manpower to process this data, making the method inaccessible to a wider audience. However, this has changed with the invention of satellite-based remote sensing in the last century, which is now an essential tool in the collection of geographic information.

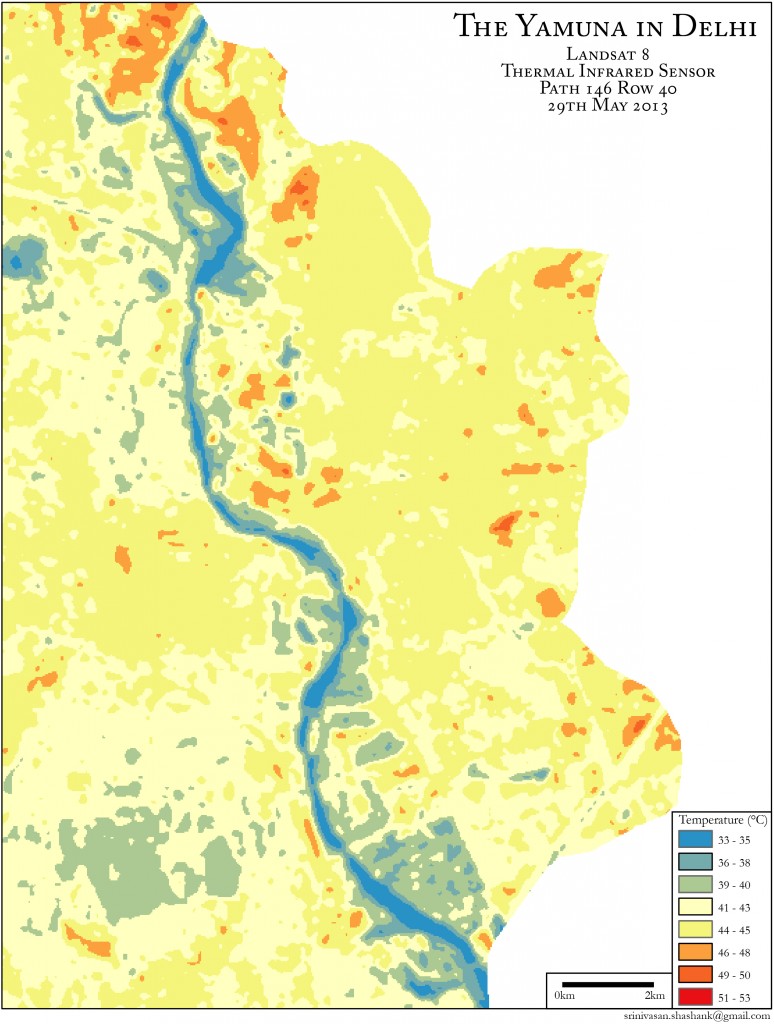

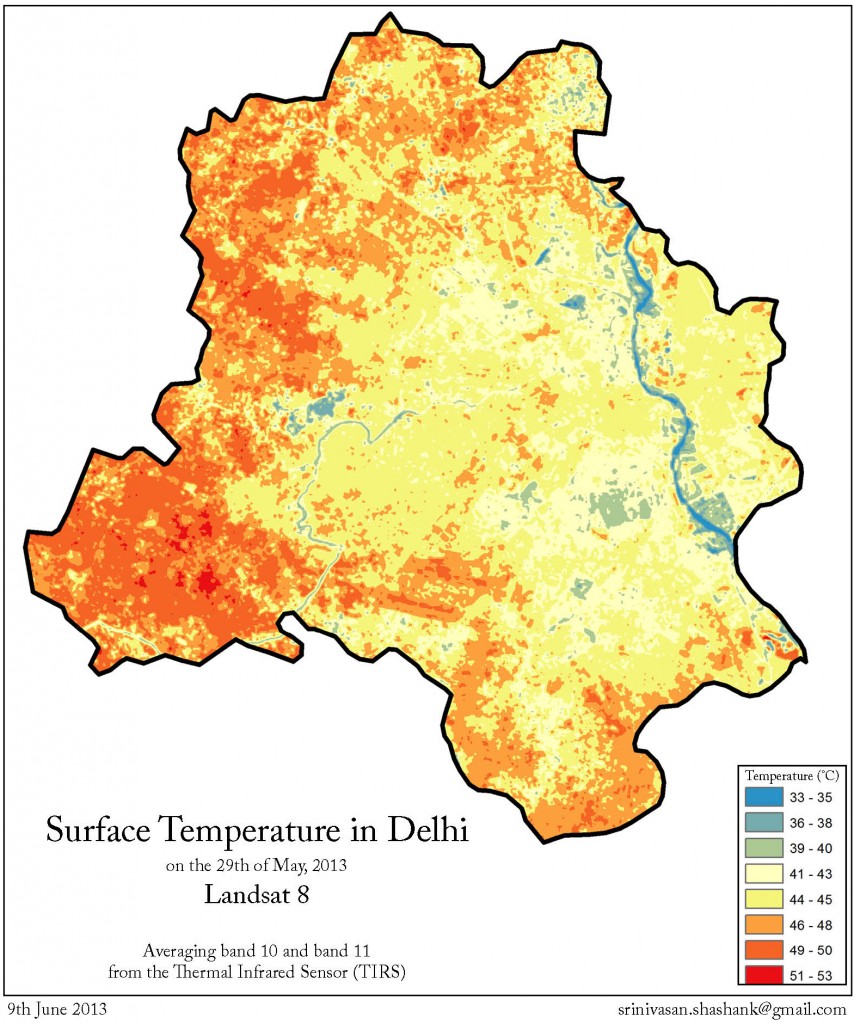

Remote sensing, the study of objects from a distance using both passive and active electromagnetic radiation, has automated the surveying method and reduced the time taken to collect this data. Increased computational power and advanced software development have enabled the creation of easily deployable GIS.

There are numerous agencies in India today, both governmental and private, that work on the various applications of remote sensing data. Chief among these applications is the study of the environment for purposes of management, conservation and protection. The Forest Survey of India produces forest cover maps of the country, and other agencies prepare or commission maps of their themes of interest.

Geographic information and environmental protection are inextricably interlinked. The identification and delineation of borders that restrict or permit access to areas, or of boundaries that define ecological extent or wildlife movement, are critical to environmental management. Controlling and containing the environmental impact of human activity requires this information to be easily accessible to environmental regulatory agencies such as the Indian Union Ministry for Environment and Forests (MoEF) and the various State Forest Departments.

Decisions taken by these agencies affect the lives and livelihoods of millions of Indians everyday. Data is obtained from various sources and used to make these crucial decisions; however, these datasets are disaggregated and difficult to visualise in their existing form. There is a strong case to be made for the digitisation of India's environmental information; in a recent judgment, the Supreme Court of India has explicitly recognised this need.

Geospatial System

Ideally, the spatial data from an application for environmental or forest clearance would be rapidly entered into the GIS; this could then be compared with other datasets such as forest cover, wildlife habitat, groundwater and distance from protected areas. Since the data from all applications will be contained within the same GIS, the cumulative environmental impact on a specific region will be rapidly estimated. This GIS could be used as a Geospatial Decision Support System (GDSS) to help regulatory agencies make transparent decisions.

Without this GDSS, government agencies will not have access to the best available tools required to enforce the laws of the land. For example, the Goa State Assembly's Public Accounts Committee recently used freely available satellite imagery from Google Earth to identify a case of illegal mining. An efficient GIS will be able to automatically flag such flagrant violations.

Europe's MOLAND project

The MOLAND (Monitoring Land Use/Cover Dynamics) system maintained by the European Commission's Joint Research Centre is one example of a functional GDSS, and was initiated in 1998. The US Forest Service also uses GDSSs for various purposes; its most recent tool, the November 9, 2011 Forests to Faucets project, “identifies areas that supply surface drinking water, have consumer demand for this water, and are facing significant development threats.”

Creating this GDSS will be a technical and technological challenge, and could be developed by private agencies, such as Google or Paladin, that have proven expertise in the design and production of such enterprise-level software. Indian government agencies such as the National Information Centre (NIC), the National Remote Sensing Agency (NRSA) and the various state Space Applications Centres (SAC) may also be able to play leading roles in this process.

An alternative production process is through the development of open-source software; an example of this process is the US-Russian government ‘code-a-thon' held in September 2011, where teams of programmers competed to create information systems for better governance. The technologies required to create a comprehensive environmental GDSS exist; implementing them will magnify the capacity and intent of environment regulatory authorities in India.

[ This article was commissioned by the Centre for the Advanced Study of India at the University of Pennsylvania and is also available on their blog. ]